|

The Impact of U.S. Aerial Reconnaissance during the Early Cold War (1947-1962): Service & Sacrifice of the Cold Warriors |

|

|||||

|

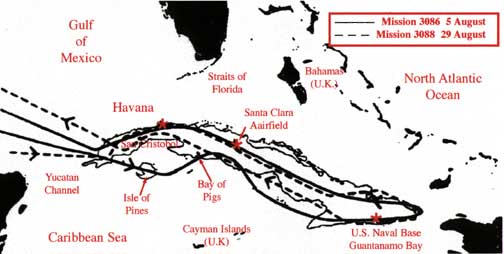

Page 1 of 5 Pages Beyond the U-2 A few of us were called into a closed meeting and given a briefing on an upcoming secret mission that would penetrate deep into Soviet territory on a ferret mission. [We] were told that the flights would be extremely hazardous and that participation would not be ordered. No one ever begged off, though everyone understood that playing chicken with Soviet air defenses was potentially deadly. I think the thing most locked into my memory is the concluding words of each ferret mission briefing, “Gentlemen, there is no possible search or rescue capability on this mission. In the event you go down and survive to be captured, every effort will be made to effect your return, but no result can be promised.” Richerd J. Meyer Space Reconnaissance, The Cuban Missile Crisis And Beyond With the shootdown of the U-2, the Soviets proved they had regained control of their air space – thus denying the U.S. a valuable source of intelligence information. The delay between what intelligence was still required and what was available to the U.S. did not last long however. Just months after the U-2 shootdown, the U.S. successfully launched its first space reconnaissance satellite. On 10 August 1960, Discoverer 13 lifted the satellite into orbit and its film canister returned to Earth the next day. Within months, satellite imagery would replace aerial reconnaissance as the nation’s most technically advanced form of intelligence. This did not mean satellite (or space) reconnaissance made aerial (or airborne) reconnaissance obsolete. On the contrary, manned aerial reconnaissance around the world would continue to provide the President and other national leadership with vital intelligence that could not be collected from space or by any other means. Even though early satellite imagery captured greater amounts of intelligence, it did not have the flexibility to collect anything other than photographic images. Early reconnaissance satellites were also restricted to flying along the orbit in which they were launched. In addition to IMINT (albeit from a lower level than satellites), reconnaissance aircraft could collect ELINT, RADINT, AND COMINT (which were grouped under the SIGINT discipline) and conduct air sampling and patrol missions. Manned aircraft also have the advantage of being extremely flexible. Commanders more easily re-targeted and redirected aerial reconnaissance platforms against targets at a moment’s notice. Aircraft could also change their flight paths in mid-mission – something satellites could not do. A last concept to keep in mind about the differences between space and aerial reconnaissance is that spacecraft are largely passive in nature. Without highly technical and powerful radar systems, neither the Soviets nor the U.S. could detect an overhead space system. During the early Cold War, the only way to gauge the strengths and weaknesses of the USSR’s air defense systems and radars was to get the Soviets to turn them on and use them. Aerial reconnaissance working alone or in tandem could spur these actions with probes and feints into Soviet airspace. Later, when ELINT satellites were launched into collection orbits, aerial reconnaissance would be used to get a reaction while space assets could monitor and collect the activity. So in the near-term, aerial reconnaissance assets would be vital in the collection of intelligence around the globe. Some target nations, like the People’s Republic of China (PRC), did not yet have the same degree of technical competence or weapons as the Soviets. The U-2 and other military reconnaissance aircraft were still relatively safe against them. In the case of the PRC, the CIA provided the Nationalist Chinese the training and aircraft with which they flew missions over mainland China. USAF RB-57’s were also used for reconnaissance in this, and other, areas of the world. During the Indian/Pakistan hostilities in the late 1950’s, the USAF loaned the high-altitude RB-57 reconnaissance jet to the Pakistani Air Force. The U-2 was used in areas of the world closer to home as well. Within a year of the guerrilla uprising which overthrew the Cuban government, revolutionary leader Fidel Castro began taking steps which moved Cuba into the Soviet sphere of influence. By 1960, the U.S. found itself with a Communist (Soviet-supported) regime just 90 miles off its southern shores. The President tasked the CIA to begin planning ways to resolve this problem. One of these efforts involved raising and training a counter-revolutionary force which could retake Cuba from the Castro government by force. Soviet Missiles in America’s Backyard: By the summer of 1960, the USSR started sending advanced weapons systems to Cuba and the CIA requested the use of the U-2 to fly over the island and collect intelligence on these weapons deliveries. The approved U-2 missions were soon expanded to include collecting images that would support the selection of a proposed invasion site. The first Cuban overflight missions were flown on 26 and 27 October 1960 from Detachment G located at Laughlin AFB, Texas. The great distances being covered (3,,500 miles and 9 hours) required the CIA to begin modifying the U-2’s for inflight refueling in support of these longer missions. (122) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Source: Gregory W. Pedlow and Donald E. Welzenbach, The CIA and the U-2 Program, 1954 - 1974, (Wash DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 1988), 202. |

|||||||

|

The CIA continued making monthly U-2 overflights of Cuba after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion to gauge the Soviet modernization of the Cuban Armed Forces. On 5 September 1961, a U-2 mission brought back photos revealing SA-2 Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) sites and MiG-21 (FISHBED) jet interceptors. Analysts suspected the presence of these two systems could mean that the Soviets were installing something of great military significance on the island. (123)

Attributions (122) Peddle, 199-201. End of Page 1 of 5 Pages, Chapter 5 — Go to Page 2 You may go to Page — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — 5 — this chapter or you may go to Cover Page — Editor’s Introduction — Overview Acknowledgments — Table of Contents Appendixes — A — B — C — D |

|||||||