|

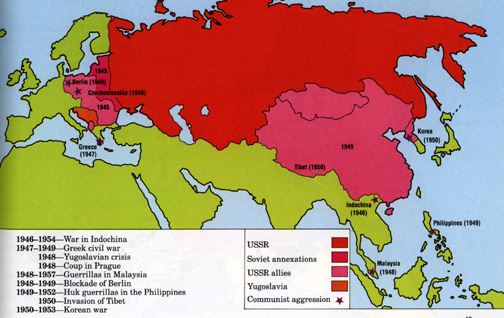

The Impact of U.S. Aerial Reconnaissance during the Early Cold War (1947-1962): Service & Sacrifice of the Cold Warriors Chapter 1 The Birth of the Cold War The Earliest Beginnings Due to the devastation of World War II and the depleted power of the Western allies, the U.S. soon found itself as the primary counterforce to a seemingly, overwhelming effort by the USSR. Exacerbating the U.S. position was the drastic and rapid demobilization of the U.S. military. By the end of 1945, the nation’s armed forces was decreased from 12.5 to 1.5 million men. Without overwhelming military manpower, the Truman administration had few tools at its disposal to stem an ever-increasing Soviet presence throughout Europe, the Middle- and Far-East. This would lead U.S. war-planners, defense officials and the administration into a reliance on the newly developed atomic bomb as the nation’s primary defensive deterrent. Before the end of 1945, U.S. military planners were asked to complete a Vulnerability Study covering the prospect of war against the USSR. In October 1945, the Joint Chefs of Staff (JCS) Paper “Strategic Vulnerability of Russia to Limited Attack” outlined a plan to destroy the USSR’s 20 largest cities with atomic bombs if the U.S. and USSR went to war. (3) Though many scholars debate what one event precipitated the Cold War, it’s true beginnings more likely lay in the series of events which took place immediately after World War II ended in Europe. These events built upon each other in a crescendo which eventually led the world to be split into two camps (or poles). One revolved around the Soviet Union and the other around the United States. Although the allies (US, USSR, United Kingdom, and France) all agreed to seek certain war reparations from a defeated Germany and to the joint occupation of Berlin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill felt President Roosevelt’s failing health gave Stalin too many concessions in dividing up postwar Europe. After President Truman came to power, Churchill sought every opportunity to influence the new U.S. President into this view as well. This effort was aided by perceived Soviet signals. In February 1946, Premier Stalin gave a speech in the Supreme Soviet which western politicos took as the most provocative and “warlike” ever given by a Soviet leader. (4) Initial U.S. Actions: With all of Europe in ruins and the USSR pressing it’s advantage in troops and position, the U.S. initiated the Marshall Plan to help rebuild Europe and give devastated European nations a better chance to stand up against a strong Soviet presence. In addition to pumping billions of dollars into rebuilding Europe, President Truman ended the Lend-Lease program and started to pull back loans and aid to the USSR. This was done in retaliation for what Truman perceived as the USSR breaking of previous postwar Europe promises and agreements and also as a means to blunt the ongoing threat of further Soviet expansion. Still suffering the drain on its economy from World War II, and trying to maintain its overseas empire, the UK government informed the U.S. on 21 February 1946, it could not continue to aid the Greek and Turkish governments in their struggle with Communist insurgencies. (5) On 12 March 1946, President Truman went before a joint session of Congress and requested $400 million for aid to Greece and Turkey. The U.S. media dubbed this action the Truman Doctrine. The request was approved by Congress on April 22, 1946 and the die was cast, clearly defining the U.S. as the primary counterbalance to the USSR in what would soon be known to all as the Cold War. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Source: Gerard Chiliand, The Strategic Atlas: a Comparative Geopolitics |

|||||

|

The seriousness of the situation was emphasized when combined with a telegram sent to Washington DC by the U.S. charge d’affairs in Moscow, George F. Kennan, the very next day. In it, Kennan stated

Kennan’s 8,000 word “Long Telegram” set the stage for identifying the Soviets as the primary threat to world peace and as aggressors on a global stage. More than any other document after the war, it enunciated the US/USSR confrontation which was to split the globe into a bipolar world. As Kennan said, the USSR was “.... a totalitarian regime bent on expansion....In general, all Soviet efforts on the unofficial international plane will be negative and destructive in character, designed to tear down the sources of strength beyond the Soviet control.” (7) An example of this would be the Soviet Blockade of Berlin in June 1948. When the USSR attempted to force the Western allies out of East Germany by closing all rail and road lines to the city from West Germany, President Truman responded to this action by using the newly established U.S. Air Force to resupply the city by air. Not only did this action begin a buildup of U.S. military might in Europe, it also addressed a real need to know more about Soviet intentions. Attributions (3) International Security, vol. 15, no 4 (Spring 1991), 171. End of Page 2 of 4 Pages, Chapter 1 — Go to Page 3 You may go to Page — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — this chapter or you may go to Cover Page — Editor’s Introduction — Overview Acknowledgments — Table of Contents Appendixes — A — B — C — D |

|||||