|

The Impact of U.S. Aerial Reconnaissance during the Early Cold War (1947-1962): Service & Sacrifice of the Cold Warriors |

|||||

|

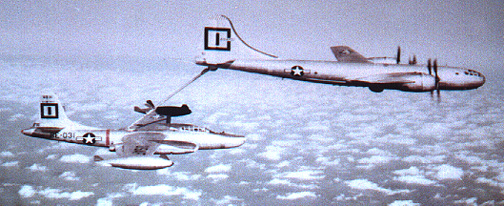

Page 2 of 6 Pages Answering the Call As the Communist Chinese entered the conflict and began pressing the UN forces back down the Korean peninsula and the threat of going to war with the PRC seemed more imminent, the USAF prepared for war against this new foe. In addition to Communist Chinese ground forces introduced in the Winter of 1950, the USSR ordered Soviet–piloted MiG-15 jet fighters, air defense radar units and antiaircraft batteries into the theater. Not only did 91st SRS ELINT operators pick up the first indications of Soviet RUS-2 early warning and SON-2 fire control radars, but a 91 SRS tail gunner scored the first ever shootdown of a Soviet MIG-15 by a Superfortress. (59) While the RB-29’s were permanently assigned to the 91 SRS, the other reconnaissance aircraft rotated into the unit from stateside units on a temporary duty basis. For instance, the RB-45 Tornado was a jet-powered reconnaissance aircraft assigned to SAC’s 91 Strategic Reconnaissance Wing (SRW) at Barksdale AFB, Louisiana. Attached to the 91 SRS as Detachment 2, the RB-45 became a workhorse for some of the most dangerous reconnaissance flights throughout the Far East. (60) The RB-45 was also the first aircraft to conduct combat air refueling operations. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Figure 3. KB-29P Refueling a RB-45 Source: Larry Davis, Superfortress in Action (Carrollton: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc.), 45. |

|||||

|

In the first jet bomber intercept in history, MiG-15’s shot down an RB-45 flying along the North Korean and Manchurian border on 4 December 1950. (61) Not only was the RB-45 tasked to fly reconnaissance missions over North Korea, it was eventually ordered to perform overflights of the PRC and USSR as well. President Truman allowed the military to more aggressively gather intelligence against these two nations because of the Korean War. Under the UN Charter’s Chapter VII, the U.S. could claim the right to fly over enemy sanctuaries of undeclared co-belligerents. Both the PRC (by its ground commitment) and the USSR (by its air force and air defense forces) could be placed in this category. (62)

As such, aerial reconnaissance missions were not just limited to the close proximity of the Korean Peninsula in the Far East. While the USN conducted most of the aerial reconnaissance of Southern China, RB-50G’s from the 91 SRS at Yokota Air Base (AB) deployed down to Taiwan from where they conducted overflights of the PRC mainland and flew missions against Communist insurgents over French Indochina. (63) In late 1952, six RB-36 reconnaissance aircraft deployed to the 91 SRS at Yokota AB. This was the first introduction of the USAF’s new B-36 to the Korean theater. While assigned to the 91 SRS, these RB-36’s conducted high-altitude aerial reconnaissance against Manchurian targets. (64) Much as the USAF RB-29’s probed the Northern USSR, Siberia and Kamchatka Peninsula for Soviet bases, Eastern Siberian coasts were continually overflown throughout this period for detection and identification of new defenses and air bases. USN P2V-3W reconnaissance aircraft flew missions in conjunction with RB-50 aircraft flying from Alaska. Between 2 April and 16 June 1952, this Navy/Air Force aerial reconnaissance team flew 8 - 9 daytime missions locating and photographing installations from the Kamchatka Peninsula, through the Bearing Straits, to Wrangel Island. A normal flight profile was for the USN aircraft to fly an ELINT mission a couple miles inside of Soviet territory while the RB-50 flew a PHOTINT mission from a position behind and a few miles outside of Soviet territory. (65) Chain of Command: The aerial reconnaissance assets in the Far East Theater were under various commands which sometimes meant they had conflicting roles, missions, and tasking. As the premier aerial reconnaissance unit in the area, the 91 SRS found itself torn between trying to satisfy the Far East Air Force (FEAF) for whom it worked directly in the theater – and SAC (where most of the aircraft and crews came from). During the war, FEAF depended on the 91 SRS for everything from visual aerial reconnaissance, bomb damage assessment, PHOTINT, and ELINT to dropping psychological leaflets on the enemy. SAC, however, also depended on the 91 SRS in the Far East to perform a number of sensitive PHOTINT, ELINT, and RADINT missions in preparation for strategic (and nuclear) air attack against the PRC and USSR. (66) In a message on 6 June 1951, the SAC Liaison in the FEAF, Colonel Winton Close, reported

While the focus of this paper is mainly on “strategic” aerial reconnaissance and its value to the national civilian decision-makers and military leaders, it should be noted there were a number of other ?tactical? aerial assets being employed in the Far East as well. In fact, after the introduction of the MiG-15 and Soviet anti-air defenses, the larger and slower bomber reconnaissance aircraft became more vulnerable. Smaller, high-speed jet reconnaissance aircraft were employed throughout the Far East theater such as the RF-80 and RF-86. In other areas of the world, aerial reconnaissance was being stepped up as well. Attributions (59) Glenn B. Infield, Unarmed and Unafraid (Toronto: The Macmillan Co., 1970) 155. End of Page 2 of 6 Pages, Chapter 3 — Go to Page 3 You may go to Page — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — 5 — 6 — this chapter or you may go to Cover Page — Editor’s Introduction — Overview Acknowledgments — Table of Contents Appendixes — A — B — C — D |

|||||