|

The Impact of U.S. Aerial Reconnaissance during the Early Cold War (1947-1962): Service & Sacrifice of the Cold Warriors |

|||||

|

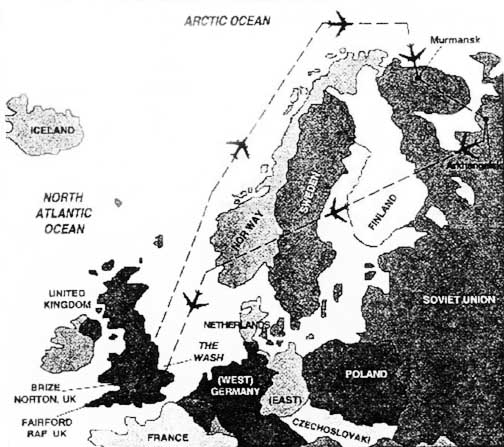

Page 6 of 6 Pages Answering the Call Closing the Iron Curtin in the Air: The Far East was not the only area in which the Soviets began to gain control over their own airspace. All of the RB-45 overflights in the Western USSR were tracked by Soviet radar in 1952 and 1953. The inability of Soviet Air Defense fighters to intercept them had much to do with lack of pilot experience, ground controlled intercept technique, and Soviet command and control. By the time of the RB-47 overflight of the Kola Peninsula in May 1954, Soviet fighter pilot experience and technique had improved. SAC required intelligence about Soviet air defense fighter and long-range bomber dispositions in this Northwestern Soviet region since this is where a U.S. or USSR strategic attack would start. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Source: Harold Austin, “A Cold War Overflight of the USSR,” Daedalus Flyer, Vol. 35, No. 1, Spring 1995, 14. |

|||||

The RB-47 aircraft commander of that mission, Colonel Hal Austin, gives evidence of Soviet air defense improvements better than any analysis or facts and figures. On that day, Col Austin relates

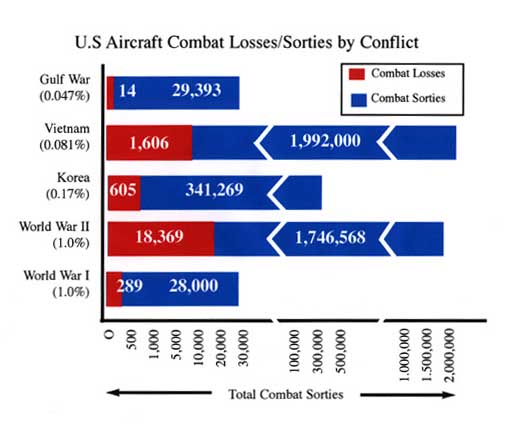

Col Austin and his RB-47 crew held off the pursuing MiG-17’s with a combination of flying skill, use of the rear-mounted gun and a little luck. Other than the critical intelligence gathered, the lesson learned from the execution of this flight was that the U.S. would need faster and/or higher-flying aircraft for future overflights. But even more serious for SAC was that solutions were needed if it planned to bring its nuclear strike force through these areas. Between 1950 and 1955, over 20 U.S. aerial reconnaissance aircraft were lost to hostile fire or other unknown (unclaimed) causes (see Appendix C.). If on par with the number of sorties flown and the casualties reported in JCS 2150/11 (one percent of all sorties lost), this number would tie with World War II aircraft combat losses as the most costly air actions in U.S. history. Of all the casualty rates accumulated in WW II, the attrition rate of aircraft combat losses accounted for more deaths (per days in combat) than Army combat infantry operations suffered in Europe or Marine Corps amphibious landings in the Pacific. (83) |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Source: Statistics by Tom Clancy, Every Man a Tiger (New York: G.T.Putnam’s Sons, 1999), 502 |

|||||

| In other words, the U.S. paid a high price for aerial reconnaissance during the Cold War, especially as Soviet air defenses increased and air defense fighter interceptors became more proficient. Becoming more and more dependent on aerial reconnaissance to fill intelligence gaps forced an even greater price in lost aircrews and aircraft. If the U.S. was to regain the reconnaissance advantage it had in the beginning years of the Cold War (between 1946 – 1950), it would need to find solutions to the increasingly more effective closed air defenses of the Soviet Union and Communist block. Attributions (82) Harold Austin, “A Cold War Overflight of the USSR,” Daedalus Flyer, Vol. 35, No. 1, Spring 1995, 16. End of Page 6 of 6 Pages, Chapter 3 — Go to Chapter 4 You may go to Page — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — 5 — 6 — this chapter or you may go to Cover Page — Editor’s Introduction — Overview Acknowledgments — Table of Contents Appendixes — A — B — C — D |

|||||