|

The Impact of U.S. Aerial Reconnaissance during the Early Cold War (1947-1962): Service & Sacrifice of the Cold Warriors |

||||||

|

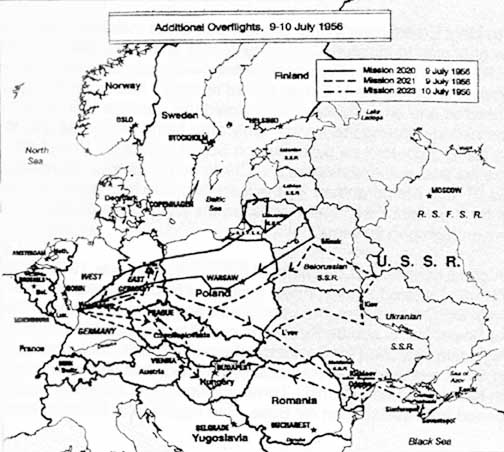

Page 3 of 5 Pages Seeking Answers: Another troubling intelligence problem that started getting more and more attention by this time was understanding the pace and scope of Soviet missile development. The first indications were in late 1954, when Army Security Agency personnel stationed in Turkey collected telemetry signals (similar to those designed by German scientists) emanating from the Kapustin Yar area. (103) The USAF again enlisted the support of the Royal Air Force and British Canbarra’s conducted overflights of this area. In September 1955, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force Trevor Gardner acknowledged that “the most complex and baffling technological mystery today is not the Russian capability in aircraft and nuclear weapons but rather what Soviet progress has been in the field of nuclear missiles.” (104) By February 1956, the USSR had tested a ballistic missile with a 900-mile range. Western media began to focus on the USSR’s advancement in weapons development, featuring articles and stories about bomber and missile capabilities and the U.S. vulnerability to those systems. As experts readily admitted, there was no defense against incoming missiles. Spurred by public attention, soon even Congressional members began asking the administration and DoD about this speculation. Even President Eisenhower admitted at a press conference that the USSR might be ahead of the U.S. (105) More fuel was added to the national security debate in April 1956 when Nikita Kruschev stated, “I am quite sure that we shall have a missile with a hydrogen-bomb warhead which could hit any point in the world.” (106) This developing Soviet missile debate, combined with a perceived Bomber Gap, forced President decision to go forward with U-2 . In the months leading into the missile debate, the U-2 finished testing and the first crews completed their training. In April 1956, the first two production aircraft were packed into USAF transport aircraft and taken to Air Base in the United Kingdom to begin operations. However, before the first missions could be launched, British political leaders pulled back their support to the program – not wanting these types of missions launched from the UK. The entire unit was packed up and moved to Wiesbaden, Germany. (107) In June, Air Force Chief of Staff, General Nathan Twinning and a delegation of USAF leaders were invited to the Soviet Union for a goodwill visit. The Soviets gave their USAF guests tours of various Soviet locations and put on an air show in their behalf. Afterwards, confronted General Twinning by saying, “Today we showed you our aircraft. Would you like to see our missiles?” When General Twinning eagerly replied in the affirmative, said, “No. We will not show them to you. First show us your aircraft and stop sending intruders into our airspace. We will shoot down uninvited guests. We will get all of yours . They are flying coffins.” (108) This was an ominous warning to officials as the CIA prepared to begin flying deep overflights into the USSR with the U-2. The first of these missions would begin in just two weeks. Project Overflight and U-2 Shootdown After President Eisenhower’s offer of the Open Skies initiative was rejected by the Soviets, the final plan to initiate U-2 overflights was finalized under the codename Operation OVERFLIGHT. One of President Eisenhower’s primary concerns was the ability of the Soviets to detect the U-2 over Soviet territory. Most importantly, if an aircraft was detected and brought down, how would this damage U.S. relations with the USSSR and other nations around the world? Only after being presented with technical details showing the U-2 couldn’t be picked up on Soviet radars did President Eisenhower give his final authorization for the CIA to begin a series of overflights in a ten-day window. (109) In a Memorandum for the Record giving final authorization for the start of the flights, President Eisenhower stressed the importance of “concentrating the [U-2] operations on high priority items.” (110) The CIA conducted its first overflight on the USSR on 4 July 1956. The first mission (#2103) was targeted against major military airfields to make an inventory of the Soviet Air Force’s BISON bombers and Leningrad’s shipyards to check on the development of Soviet naval submarines. The next day a second U-2 overflight (mission #2104) again searched for Soviet bombers at airfields, took photographs of BISON training fields and arsenal at Ramenskoye airfield, and flew over missile and rocket plants in Kaliningrad and Khimki. Three additonal U-2 missions were flown in the initial 10-day period from Weisbaden Air Base (See Appendix D for complete list of U-2 overflights). (111) The official Soviet protest soon followed the first U-2 overflights. On 10 July, the Soviets delivered a note to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow which was quickly translated and relayed to President Eisenhower. In it, the Soviets outlined the exact dates and times of these intrusions and concluded by saying

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Source: Gregory W. and Donald E. , The CIA and the U-2 Program, |

||||||

|

President immediately ordered the CIA to terminate any additional . While the Soviet inclusion of specific dates, times and cities indicated they could track the U-2 by radar, the misidentification of the violating aircraft as a “twin-engine jet bomber” probably indicated that they could not reach the U-2 to visually identify it. In an official reply sent on 19 July, the U.S. stated that no “military” aircraft had overflown the USSR. (113) While this was truthful (since the U-2 was a civilian, not military aircraft) the incident highlighted the need for a review of the program before overflights could resume

. Attributions (103) Richelson, 264. End of Page 3 of 5 Pages, Chapter 4 — Go to Page 4 You may go to Page — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — 5 — this chapter or you may go to Cover Page — Editor’s Introduction — Overview Acknowledgments — Table of Contents Appendixes — A — B — C — D |

||||||