|

The Impact of U.S. Aerial Reconnaissance during the Early Cold War (1947-1962): Service & Sacrifice of the Cold Warriors |

|||||

|

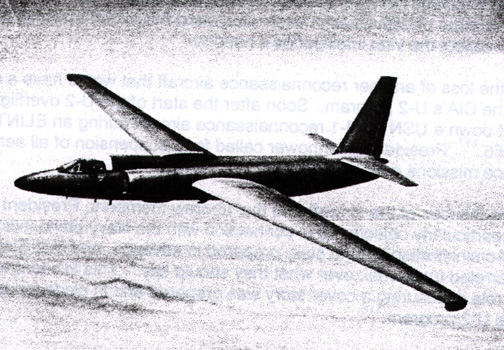

Page 4 of 5 Pages Seeking Answers: Though President Eisenhower was extremely concerned about the Soviet ability to track the U-2, the great wealth of intelligence taken from the first series of photographs had an immediate effect on his attitude regarding the usefulness and value of this aerial reconnaissance asset. The first huge benefit of Project OVERFLIGHT was to disprove the Bomber Gap. No BISON bombers were photographed at any of the nine Soviet Long Range Aviation (LRA) bases overflown in Eastern Europe and the USSR from 20 June through 10 July 1956. While this in itself did not mean the Soviets were not producing and fielding LRA bombers, it proved the Soviets did not have as many bombers as analysts had estimated. With these “million dollar photographs,” the administration would be able to cut back on the USAF’s additional funding requests for the B-52’s SAC stated were needed to catch up with Soviet bomber production. (114) Although President Eisenhower realized the value of the U-2 intelligence, he did not allow the effort to expand and maintained firm control over Program OVERFLIGHT himself. Continually pressed for more overflights from the CIA and DoD, he did not approve additional flights over the USSR if the need for specific pieces of intelligence didn’t outweigh the risks being taken in rising tensions in the international community. During the almost four years of Soviet U-2 overflights, President Eisenhower only approved 24 missions. Several U-2 missions were flown along the USSR’s borders and over other nations. A few other U-2 missions conducted unplanned shallow overflights. Other detachments, under cover as Provisional Weather Reconnaissance Squadrons (WRSP), were established at Incerlick AB, Turkey; Eielson AFB, Alaska; and Atsugi AB, Japan. These various locations allowed the CIA to target areas of high interest with the U-2. The first ELINT-configured U-2 began flying missions along the southern and central borders of the USSR. Some U-2 flights were flown in conjunction with other USAF aircraft (like the RB-57) to collect some of the first airborne telemetry intelligence (TELINT) from Soviet missile launch guidance systems. A sample of some other U-2 overflights conducted include:

Missile Gap: The most pressing national security concern which kept forcing President Eisenhower into authorizing more and more U-2 flights was that of Soviet missile development. Premier Kruschev’s speeches describing how Soviet ICBMs were coming “out of the factories like sausages” and how the Soviet Union would “bury” the United States with its rockets was not all bluster. The USSR tested its first Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) on 3 August 1957. Given the NATO codename SS-6 (SAPWOOD), the Soviets used this same type of rocket booster to launch mankind’s first satellite (SPUTNIK 1) into orbit on 4 October 1957. By September 1959, the USSR had succeeded in reaching the moon with an unmanned rocket. (116) All of this did not bode well for an American society that was getting daily media doses describing how dangerous these developments were for the security of the United States. Related Aerial Reconnaissance Losses: The fact that aerial reconnaissance had already dispelled the bomber Gap was not publicly disseminated due to the secrecy of the U-2 program. Even within the Federal Government, many leaders were not let in on the fact that U-2s were flying over the Soviet Union. This was particularly disturbing to Congressional members who could not understand why the CIA and DoD were suddenly revising their Soviet strength figures downward. In addition to periodic U-2 overflights, other USAF and USN aerial reconnaissance aircraft were collecting intelligence information about the developing Soviet missile program. The Soviets shot down a newly-developed RB-50 SIGINT platform in the Far East in September 1956 with all 16 crewmen killed. On 2 September 1958, Soviet fighters shot down another new SIGINT-configured C-130 aircraft over Soviet Armenia. The entire reconnaissance C-130 crew of 17 was lost as well – two new platforms, almost exactly two years apart. These two different (yet similar) cases, along with the large number of casualties in each, illustrated the extent to which the USAF was willing to go to collect the vital intelligence it needed. It was the loss of another reconnaissance aircraft that would have a different type of impact on the CIA’s U-2 program. Soon after the start of U-2 overflights, the PRC Air Force shot down a USN P4M-1 reconnaissance aircraft during an ELINT mission on 22 August 1956. (117) President Eisenhower called for a suspension of all aerial reconnaissance missions over and around Communist areas. Besides the loss of the aircraft and the 16 crewmembers, President Eisenhower said what he particularly objected to in connection with the Navy plane incident was that the Administration had no story prepared in advance, and that State and the Services “quarreled for a week over what they should say.” This incident would play a predominant role in ensuring a cover story was prepared and in place for such an incident in the U-2 program. (118) Shootdown of U-2 over the Soviet Union: On 1 May 1960, the CIA launched a U-2 mission over the Central USSR to search for and photograph various missile installations. What was unique about this particular mission, other than the fact it was being staged from Pakistan, was that it was to be the first complete overflight of the Soviet Union from one end to the other. (119) This 3,800 mile, nine-hour overflight was to take the CIA pilot from Peshwar, Pakistan to Bodo, Norway. Everything during the beginning of the flight appeared normal, as pilot Francis Gary Powers recalled

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Source: Larry Davis, U-2 Spyplane in Action (Carrollton: Squadron/Signals Publication, Inc. 1988), 2. |

|||||

|

What Powers didn’t know is that, after years of frustration and trying to develop new weapons and techniques, Soviet air defense forces were ready for him. According to soviet sources, some fourteen surface-to-air SA-2 GUIDLINE missiles were fired simultaneously at his U-2 while a number of MiG-19 jet fighters tried zoom climbing to reach him with their guns. Exploding SA-2 missiles managed to damage the U-2 enough to bring it down (in addition to shooting down one of the MiG interceptors). The soviets captured Gary Powers and managed to salvage enough of the aircraft to prove to the world that the U.S. was engaged in clandestine aerial reconnaissance over their territory. (121)

Attributions (114) DCI Allen Dulles coined the term “million dollar photos” some years after the initial U-2 flights. In reality the U-2 reconnaissance photos were worth much more considering their use to scale back the defense expenditures many believed were needed to catch up with Soviet weapon production. End of Page 4 of 5 Pages, Chapter 4 — Go to Page 5 You may go to Page — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — 5 — this chapter or you may go to Cover Page — Editor’s Introduction — Overview Acknowledgments — Table of Contents Appendixes — A — B — C — D |

|||||