Men share tales of reconnaissance missionsStory by James Kirley, Special Projects Writer

|

||||||||||||||

|

Walk through the pre-dawn cold at Yokota Air Base in Japan 50 years ago and push open the door to its mess hall, feel the warmth and smell the food as you walk through the dim expanse towards a pool of light in one corner. Beneath it, a flight crew is bent over 4 a.m. breakfast, part nutrition and part steeling of nerves. Earl Myers, 1st lieutenant, U.S. Air Force, arrives carrying his own fresh tomato. Bought from a Japanese vender outside the base, he slices it over government-issue bacon and eggs using a survival knife pulled from his flight suit. Myers is 27 and can’t know that he’ll survive another armed reconnaissance mission over North Korea at the controls of his RB-29 bomber. |

||||||||||||||

| One year later, 30-year-old Capt. Jack Romney would trudge through the same pre-dawn cold to the same mess hall, preparing to fly the same aircraft. Myers had passed command of his bomber to Romney in April 1951 the two Air Force officers barely knew each other in Japan.

But Myers recently learned his squadron mate was living in Vero Beach and phoned Romney. "When I called him, I asked, ‘What were you doing 50 years ago?’ " said Myers, now 77. "You could hear the gears turning in his head." |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Fifty years ago this weekend, just when Americans thought the 5-month-old Korean War was about to end in United Nations victory, Chinese troops attacked on the side of North Korea.

American Gen. Douglas MacArthur had assured President Harry Truman and the Joint Chiefs of Staff that China was unlikely to enter this war. While his troops pushed through North Korea to within 50 miles of China’s border, MacArthur said China could not field more than 60,000 troops to support its communist neighbor and that those could be slaughtered by U.S. air and artillery. In fact, 300,000 Chinese troops had quietly crossed the Yalu River into North Korea during November 1950. They marched by night, using trucks and ponies to haul supplies and camouflaged themselves into the hills before daybreak. Myers, flying his reconnaissance bomber over the area, said their movements were not discerned by air. "I didn’t see any big mass of troops," he said. Nobody did. Allied commanders learned the true size of the Chinese force the night of Nov. 25-26, when it poured over Allied battle lines. American soldiers made fighting retreats south and the war essentially stalemated at the 38th Parallel where it began. |

||||||||||||||

| Romney, now 80, doesn’t remember any bad nerves at his flight crew’s breakfast table. "I had a pretty cool crew," he said. "This is something that I regularly counseled them on: I just explained to all of them that they shouldn’t imagine anything." There was a bombardier in another flight crew who squeezed lemon juice over his breakfast eggs. Romney can’t recall the man’s name, but remembers the reason for his strange taste. Six years earlier, the bombardier had parachuted from a crippled B-29 during a World War II bombing raid over Japan. "He had been a prisoner of war," Romney said. "He had been hauled through the streets of Tokyo with a rope around his neck on the way to a POW camp." Now, fighting butterflies in his stomach, the bombardier used lemon juice to cut through greasy food and fight off nausea. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| The war had began in June 1950. Under North Korean attack, American and South Korean soldiers formed a 5,000-square-mile perimeter protecting the sea port of Pusan. It would be the gateway for fresh Allied armies. The North Korean Army, knowing this to be the plan, was desperate to hurl the U.S. and South Korean forces in the Sea of Japan before those reinforcements arrived. Ammunition and food for the attackers had to travel hundreds of miles from North Korean factories and ports by train and truck convoys. The 91st Reconnaissance Squadron, Myers’ and Romney’s outfit, flew across the Sea of Japan to hunt them. "We were looking for targets of opportunity," Myers said. "That included military convoys, trains, (fuel) tank farms and moving tanks scurrying from the open area to cover." A favorite tactic was to follow railroad tracks until you found a train. Myers then would fly the huge bomber 500 feet off the ground, while his crew poured machine gun rounds into it. "They’d be doing about 30 (kilometers per hour) and we were doing about 300," Myers said. "We’d fly alongside and strafe them. They had a machine gun on about every other train car. The soldiers would be firing on us with rifles and machine guns as we passed. "When a steam engine was hit by .50-caliber armor-piercing bullets, they’d penetrate all the way through and it looked like Old Faithful erupting." |

||||||||||||||

| Before each mission, Myers and Romney would walk around their massive propeller-driven aircraft, checking its four supercharged engines for excessive oil leaks or open access panels. Inside, crew members were checking their stations. Myers remembers the howl of his aircraft’s auxiliary power unit, feeding electricity through the waking beast until its four 18-cylinder piston engines coughed smoke and came alive. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

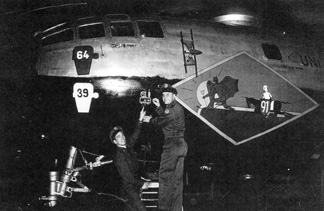

| The aircraft was known as the "Niner-Two-Niner" to the men of the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, shorthand for the last digits of the serial number on its tail. The crew dubbed it the "Honey Bucket Honcho" and hired an artist to paint a large mural on its starboard nose. It depicted most of the 13 crew members as a haphazard bunch of Sad Sacks, piloting a ramshackle contraption made of wood and nails and baling wire.

Both Vero Beach veterans have strong memories of their Korean War missions. Pilots and flight crew in forward stations crawled aboard through a hatch in the nose gear wheel well. Myers said the first thing you saw when you poked your head inside the bomber was a bank of instruments used by the flight engineer. Leaving the runway in Yokota, RB-29 crews would begin 12-hour missions by heading west, climbing through the dark sky for arrival over Korea at daybreak. "The first time you climb up through a solid cloud level, and then you pop out and it’s a bright, shining day it’s a new world," Romney said. The mood was somewhat relaxed while flying over the Sea of Japan. "There might be a little bit of chatter on the intercom," Romney said. He remembered one flight during which a crewman in the aft compartment had freshly returned from a night on the town. He had been swilling beer and eating kimchi, a Korean delicacy made of pickled cabbage, peppers and garlic. "The guys were ribbing each other, taking a vote to see if they should throw him overboard," Romney recalled. |

||||||||||||||

| The mood changed as the Korean coast loomed ahead. A test firing of guns usually signaled the beginning of business in earnest. Then carrier-based U.S. Navy fighters would pop out of nowhere Romney said they never used the same radio frequency and always arrive without warning. Bomb crews sometimes were welcomed into enemy territory by name. Myers said spies near Yokota Air Base apparently radioed ahead with aircraft tail numbers, squadron insignia and descriptions of nose art. "It just wasn’t very comfortable when you heard your name coming out of an enemy (high frequency) radio," Myers said. Romney recalled watching enemy MiG-15 fighter jets tearing into another RB-29 in the distant sky, his own jet fighter cover unable to assist because of low fuel. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

fly by RB-29 over North Korea Ctsy. Earl Myers |

||||||||||||||

|

Both men survived to pursue successful postwar careers. Romney, who logged hours in legendary P-51 Mustang fighters as well as RB-29s, left the Air Force in 1954. He took a job at U.S. Steel, trading those intense glimpses of sunshine at 30,000 feet for a normal family life. Myers stuck with flying for life. He traded aging RB-29s for sleek six-engine B-47 Statojets and racked up flight hours in 52 different types of military aircraft before retiring as a colonel.

Both men recalled their Korean War service as an odd mix of the dangerous and the normal: Day trips from the comfort of an air base, over a combat zone where soldiers froze in foxholes, dodging radar-guided anti-aircraft artillery and returning home for supper. "After the mission, they’d give you a shot of whiskey and you’d go over the officer’s club for a nice dinner," Romney said. "It was just a strange contradiction." Home - Contact Us - Cold War Hist. - 91st SRS Hist. - Stardust 40 Mission Story |

||||||||||||||