|

U.S. Naval Aviation In the South Pacific during WW II Featuring the Lexington Aircraft Carrier The Battle of the Marianas — June 1944 Chapter 1 Page 6 of 7 Pages |

||||||||||||

| June 20: Through the whole of yesterday’s fight, no one ever actually sighted the Japanese ships; indeed there was still some question after the biggest air fight on record, as to whether Widhelm could even collect his thousand-dollar bet since, technically, there was no proof that it had been a carrier duel at all.

Our searches went out early in the morning but up to 3 o’clock in the afternoon, none of them had any success. Having stayed up most of last night, I went below for a nap. At about 4 I was wakened by the loudspeaker directing Lieut. Commander Myers to dial 006. Such messages, I had learned, usually meant activity of an interesting sort so I was on the alert for what would be coming next. The loudspeaker presently said: “All fighter pilots report to the ready room immediately.” Then it said: “All torpedo-bomber pilots report to the ready room immediately.” Then it said: “All dive-bomber pilots report to the ready room immediately.” In flag plot, I learned that search planes from another carrier had at last found the Japanese fleet 250 miles to the northwest of us. Our previous searches, sent farther out, had missed them entirely. Apparently the Japanese had stopped to fuel heading into the wind from the east and, being much closer to us than we had any right to expect, had escaped detection on this account. Mitscher had had his haircut and also made a plan. He called for an immediate combined attack of 100 or so dive and torpedo bombers, escorted by fighter planes in case there were any fighters left on the Japanese carriers. The attack was timed to leave at about 4:30, reach the Japanese about 6:30 and get back to our carriers a couple of hours later. The last part of the plan was even riskier than the attack itself. At night, carriers are hard to find and landings on them difficult in any case. On this occasion, our planes would be nearly out of gas, since the attack was to be made with heavy loads at close to maximum range. The objective however, seemed to justify the risk. [Click here for a view of the Attack Map layout with a quick return to this page.] The interval of four hours or so between the time the planes took off and the time they began to return was, on our carrier, a period of suspense even more intense and unrelieved than the periods waiting in yesterday’s battle. No word came back until around 7 o’clock when a message was relayed from Lieut. Commander Ralph Weymouth, commanding our dive bombers, to the effect that hits had been made and fires seen on four Japanese carriers. General quarters had been sounded. Admiral Mitscher sat on his windy bridge rubbing his chin from time to time. Between 7 and 7:30 he smoked three cigarettes, taking them carefully from his leather case and lighting each with a wooden match, cupped under the box, on the first attempt. Shortly after dusk, a flight of four combat patrol planes came in to our deck and others landed on other carriers. At about this time also the lights of the first planes returning from the strike at the Japanese fleet began to sparkle in the west like little green and red jewels against the last dim light of sunset. |

||||||||||||

| Before landing on a carrier, planes circle the ship and come in low over the stern where an extremely responsible officer directs them with two small, brightly painted paddles, which he holds in outstretched hands. At a certain point, the landing signal officer makes a gesture which tells the pilot to cut off his motor. It is a cardinal rule of carriers that the pilot obey instantly. His plane then drops to the deck where a hook affixed under its tail catches one of several cables stretched across the deck, bringing it to an abrupt stop. Deck hands disengage the cable, the plane taxies toward the bow and, as it does so, the signal officer on the stern flags in another one. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

A Hellcat fighter comes in to land. The pilot has throttled back his engine and extended wing flaps in order to slow down. His hook trails behind, ready to engage one of the wires strung across the deck. |

||||||||||||

|

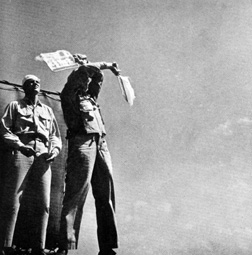

The landing signal officer indicates with paddles whether the plane is too high or too low, when to cut the engine. The pilot must obey instantly. These two photos ctsy. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

If the approach is not satisfctory, the signal officer holds his paddles overhead, crossing and uncrossing them as a “wave-off”. |

||||||||||||

| Tonight as the ring of planes circling our deck grew larger and larger, everyone on the ship knew that all of the planes in the circle were down to their last few drops of gasoline. The great hazard of night landings is a deck crash which interrupts the rhythm of the landing intervals. Our first half-dozen planes landed safely. The seventh was a visitor from another ship — on such occasions pilots are ordered to land on the first carrier they spy and our deck, being bigger than most, attracted more such guests than any other. This pilot came in high. The signalman on the stern gave him a wave-off, i.e. a signal instructing him not to land. Because he was wounded, out of gas and dead tired, the pilot ignored it and cut his motor a moment later than he should have. The plane consequently missed the cables. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Ctsy: Life Mag., dated 6/17/44 |

||||||||||||

| It was stopped instead by parked planes at the bow. Riding into one of these, its propeller killed a rear-seat gunner, who a few seconds before had felt himself safe at last from the most dangerous flight he had ever undertaken. Searchlights were turned on the wreck from the bridge. Within 10 minutes another corpse, that of a deck hand, had been pulled out of the wreckage, and the rhythm of the landings was resumed.

The deck crash on our carrier was the most spectacular single incident observable on our ship. It was a microscopic detail in an hour of such eerie and eccentric horror which, for the pilots who went through it successfully, outweighed the appalling risks of the mission which had preceded it. Shortly after the deck crash, I felt my way down a darkened ladder and along a dim and winding passageway to the dive-bomber ready room. On the way I passed the ship’s surgeon and several stretcher-bearers, lowering the wounded men to the hangar deck to be taken to sick bay. A few feet farther along, behind a door, still on stretchers but completely wrapped in sheets were the bodies of the two men who had been killed. When I reached the ready room, Weymouth was telling an intelligence officer about the bombing of the fleet. All of our pilots he said had started back with him except one and most of those who had not landed on our deck were presumably safe on other carriers or in the nearby water, where destroyers were sure to find them. The pilot who had been lost — shot dead in his cockpit by a pursuing Japanese fighter — was the same one who, three days ago, had taken me with him in his dive-bomber over Saipan. Chapter 1— End of Page 6 of 7 Pages — Go to Page 7 Page —1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — 5 — 6 — 7 Or This Story’s Cover Page — Editor’s Introduction — Table of Contents Fred Gwynn’s “Torpedo 16” — Chapter — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 Or Home - Contact Us - Cold War Hist. - 91st SRS Hist. - Stardust 40 Mission Story |

||||||||||||