|

Fred Gwynn's Chapter 2 |

|||||||

|

||||||||

|

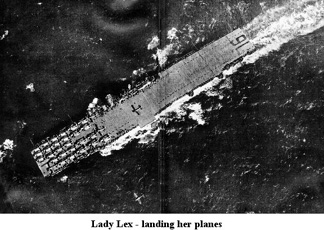

It takes three minutes to walk the length of the Lexington's flight deck, twenty minutes for a novice to get from the Junior Officers' Bunk-Room in the focsle to the ready-room amidships opposite the island, and it took half a month to get the Lex out of Norfolk after we boarded her there. Once a carrier has tied up at Pier 7, it is almost impossible to cast off. And no air group leaves Norfolk without making a certain number of taxi trips from Pier 7 to East Field and back, driving planes with hot engines over the twisting two-mile route. But it was spring: the leaves were out, the Virginia air was warm, and the lovely Norfolk N.O.B. Officers' Club was just a few blocks from Pier 7. Wifeless, with short haircuts and in gleaming white uniforms, Torpedo 16 swaggered through the festive evenings as if it had just brought the Lex back from a year of fierce combat. We were carrier pilots at last, even if we'd only made three landings aboard her so far. (I had gotten five or six wave-offs on my first landing, which had made me wonder just how long I could continue swaggering.) But it was a legitimate pride one felt in the Lex. From the air, she seemed a tiny model of the old Monitor and a pilot aloft found it difficult to believe that a few hours before he had eaten and slept and prowled within that minuscule flotsam. But if he were returning about midnight from a date in Norfolk, and had to walk the length of Pier 7, he'd get a stunning look at the ship's ponderous hull, and an opposite extreme impression of size. The stern was barely visible from the pier area near the bow, and unless there was a moon, the topmost radar antennas could not be seen above the truck lights. Anchored queen of the strange shipping there, the Lexington still seemed to be resting on the bottom. You feared that she was displacing more water than would float her. Yet she would and did float, and one day early in May of 1943, she shoved off on a shake-down cruise. It was a relief to steam out of Hampton Roads and turn right instead of left, for we'd been in the Navy long enough to know that we very well might be on our way back to Quonset or even back to Pier 7. But after a lapse of time suitable for ridding the ship of spies and stowaways, Captain Stump hit the bull-horn long enough to announce that we were underway for the Gulf of Paria, which lies between the British island of Trinidad and the Venezuelan coast of South America. Now, Voyager, sail thou forth, to seek and find. |

||||||||

| Indeed the first operational flight we made consisted of seeking and finding - subs out two hundred miles from the ship and then finding the ship, which, of course does not remain in the same place you left her. There was some doubt in my mind as to whether the navigation I'd been hacking at for the past year would actually work for such a long distance from and to a relative base, but it did work, and so did everything else. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

The catapult actually lifted seven tons of airplane from a standstill on the deck to a speed of eighty knots in the air, and the arresting gear actually stopped seven tons of plane from seventy knots in the air to a standstill on the deck. These hydraulic compression devices perfected by the inventor Sperry still seem like miracles to me.

As a historical fact, the dawn came up every day - both the slow Atlantic illumination and the slow military awakening to infinite wisdom. We found out that we had to get up at 0430 on the carrier; that we really could get out of sight of land; that it was hot below decks; that while the Lex rarely pitched or rolled, the destroyers in the force actually buried their noses up to the bridge when there was a running sea; and finally, that this trip was a shake-down for the pilots as well as the ship. This last discovery was shocking. Though Torpedo 16 was aboard a capital carrier, it was still in a training period, and actually had necessary provisions for losing pilots, through accidents and selection. By the time the Squadron reached Trinidad, it was obvious that this was the first and last cruise on a carrier for some pilots. When I realized I might well be included in this bunch, I thought back on my Norfolk swagger and Quonset omniscience, and began to eat humble pie. But most of the pilots in the Squadron were doing well, and the unit began to look as though it could some day go into combat with confidence and effectiveness. For one thing, we had a big pow-wow in the ready-room one afternoon that sold our bosses on the Lauderdale doctrine of torpedo attack. The next day Cap'n Bob Isely appeared with an improved and defined distillation that seemed to meet all the contingencies of dropping torpedoes on a maneuvering target. His plan was clear and scientific, it allowed for all the rigid performance impossibilities of the TBF and the aerial torpedo, and it placed the success of the attack squarely on the shoulders of each pilot. Torpedo 16 could now assure itself that its Skipper was a reasonable, military man. Making a good torpedo attack on a ship entails the same problem as making a tackle on a halfback in an open field. The direction, speed, and distance of relative motion between the attacker and the target changes constantly, with the additional factor of altitude in the pilot's attack. The torpedo-bomber discovers that a smart carrier can reverse her field in the same way as a smart ball-carrier can, and that she doesn't have to bother with trying to make forward yardage. A further difficulty comes in the fact that a torpedo-pilot tackling a ship may have a block thrown on him by the interference, and very likely he won't be able to get up from it for the next play. At any rate, Torpedo 16 finally got an attack plan that looked good on paper and that actually worked when we dropped real torpedoes against the Lex in the Gulf of Paria a few weeks later. It was a real triumph to score satisfactory (though simulated) hits on the agile carrier, which could turn on a dime when Capt. Stump laid her over on her side. But the most impressive and personal dawn we witnessed on that shake-down cruise was the agonizing realization that flying, and especially carrier flying, was and is a damned dangerous occupation. The fighter pilots suffered the most accidents, for they were still flying the F4F, a sturdy and efficient plane in the air, but an erratic insect when it came to light on the landing deck. Three fighters crashed into the barrier that is designed to palliate the vagaries of pilot and/or arresting-gear; three of them plunged into the briny, sometimes at the expense of the pilot's life; four cracked up on the Army field on Trinidad that we sometimes used. That makes ten or a dozen planes either completely lost or made unsafe by major damage. Two TBF's took off and hit the water just off the bow, and one got fouled up on a landing and took the radioman to the bottom when she went in. A dive-bomber pilot spun in fatally on a night landing. End of Page 1 of Chapter 2 — Go to Page 2 you may go to Introduction — Table of Contents Chapter — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — Epilogue — or Go to the Lexington Stories Cover Page Or Home - Contact Us - Cold War Hist. - 91st SRS Hist. - Stardust 40 Mission Story |

||||||||