|

Fred Gwynn's Chapter 4 |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

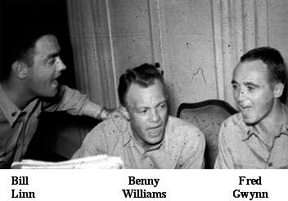

| For once the Navy did not leave us to our own devices in the matter of recreation. Pilots and flight crewmen were dumped into the ubiquitous cattle-wagons and carted off to Waikiki to the Royal Hawaiian Hotel for a couple of nights. This was our first introduction to Hawaiian areas outside the Naval Air Stations, and it was not disappointing. The Royal is a garish but comfortable building, and the Navy has been able to maintain a great deal of the lavish peace-time atmosphere. Bill Linn and I had a room, at a cost of one dollar per night, that had gone for $70 a day before the war, according to the card on the door, though it's hard to believe. Down on the terrace we saw our first hula exhibition, and were somewhat surprised to find that the ritualistic dance is really an entrancing spectacle. Hawaiian girls (or the indecipherable girls of Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, and Filipino extraction who populate the Islands) are mostly pretty when young, and all of them know the patterns of enough hulas to put on professional performances. I understand that the modern gals have somewhat debased the ancient Hawaiian choreography, but you can't tell me that the core of the whole business is not a mildly aphrodisiacal impulse. Anyway, it's good.

The liquor situation wasn't so good, though the officers were saved by being able to buy weekly rations at Pearl Harbor, and there is an officers' club at Waikiki. But the poor enlisted men, as always, got the wrong end of the deal, their only source of alcohol being beer sold in taverns or the foul imitation bourbon and gin made in the Islands and sold only to civilians. Sailors have to pay as high as $15 a bottle for the privilege of acquiring a mild glow and usually a violent series of stomach spasms. But it was a change. We had a good time at Waikiki, swimming, talking over the raid on Tarawa, knocking ourselves out with "fog-cutters" and charcoal-broiled steaks at Trader Vic's, and wandering through parties at the Seaside Bungalows. The only trouble was that we didn't know any women in Oahu, and it was getting towards the time that we do. Back at Barber's Point for the rest of the week, we continued the party-party, with adequate time out for flying, tennis, and swimming in a marvelous inlet where the waves would throw you upright on the beach. The food was pretty bad at Barber's, and Torpedo 16 hit on a diverting custom that became very popular. At the sugar plantation store in the near-by town of Ewa, we bought large supplies of sardines, caviar, Vienna sausage, sardines, deviled ham, pate de foie gras, olives, sardines, tuna fish, smoked herring, pickles, avocados, more sardines, and crackers. |

|||||||||

| For no particular reason, this supply in bulk was referred to as "17,000 fish," in one of those esoteric phrases that derives from some chance expression encountered in a minor moment. Every night we had a party in someone's room in the B.O.Q. After much singing, hunger would seize us, and the lucky host would break out a can-opener and 17,000 fish. About 2300 everyone went to bed, leaving the host's room smelling like Fulton Market and the collective squadron stomach laboring overtime to get ready for breakfast.

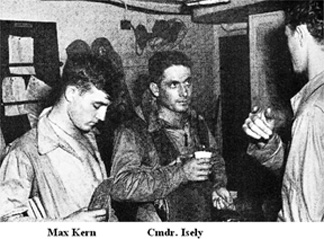

About this time it became noticeable that the Squadron had, through the communal agency of battle and brawl, become pretty well welded together. The Skipper and Exec, Isely and Sterrie, had proved to be first-rate combat leaders and had finally come around to making themselves integral parts of our parties, instead of merely guests. That mysterious regeneration signified by the universal use of first names had hit the squadron at last. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| It was also now apparent that the squadron could be logically divided into two main groups, although it is an actual fact that there was little or no rivalry between the two groups, and no cleavage whatsoverer in time of combat operation. It was not until Jaunary that Travis Oliver publicly and accurately labeled these two groups “drunks and athletes,” but the division was obvious long before. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| The Skipper and the Exec were neither Drunk nor Athlete, because they were responsible enough to be both. I have already told how gloomy, eager, and self-harassed they appeared to us junior officers at Quonset. Well, they changed, especially Bob Isely. I don't know what did it, but he turned from an ogre into an approachable human being, from a sour-puss into a somewhat humorous character, from a Senior Officer into a Fellow-Pilot. By the time he took over Torpedo 16, Lt.-Cdr. Isely had been married ten years and had a five-year-old daughter and a two-year-old son. He also had a stern devotion to his calling and a natural tendency to solve most problems by means of attack. He always wanted to be first in everything, though he was by no means an egomaniac. It was just that he was endowed with an over-charge of energy, was in a position that usually demanded vigorous action, and never hesitated to take the initiative. Bob actually liked to go into battle, and he was utterly fearless when he got there. He always stayed over the target as long as he could, and although I thought he sometimes took unnecessary risks, I realized that they could generally be justified on the elastic grounds of military achievement. Like all good leaders, Bob Isely never expected anyone to do anything he wasn't doing. Most of us really wanted to get off as lightly as possible, but the Skipper always wanted the heaviest assignments. There is a certain smug happiness now just living comfortably from day to day. Another attack is coming up, probably a big one, and I hope I can do some big damage. But while I do wish to protract any military usefulness I'm bound to have accumulated in nearly 2 years of the Navy, and while I still have plenty of daydreams about marriage, teaching, traveling, music, New York, Nantucket, and drinking, I feel I'm lucky to be in a position to take "a sudden and speedy end" calmly. After all, I'm almost 27, have been remembering, and noting my acts for 10 years, have been in love strongly, have had many parties, and have used all my talents to the dilettantes advantage and pleasure, and without, I think, hurting many people. If I get killed now, I shall escape those 3 calamities of age that Eliot speaks of: "the cold friction of expiring sense without enchantment," "the conscious impotence of rage at human folly," and "the rending pain of re-enactment of all that you have done, and been, the shame of motives late revealed ...." These seem to me to be serious drawbacks to living, and inevitable ones to a thinking reed. And yet there is the will to live, to toss the dice, and see what happens. Having met the enemy, finally, our collective futures will now be met with a combination of fear and excitiment. But we are the men of Torpedo 16, aboard the U.S.S. Lexington, and tomorrow the sun will rise and we, most definitely, will shine. End of Page 4 of Chapter 4 — Go to Epilogue Page — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — This Chapter you may go to Introduction — Table of Contents Chapter — 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — Epilogue — or Go to the Lexington Stories Cover Page Or Home - Contact Us - Cold War Hist. - 91st SRS Hist. - Stardust 40 Mission Story |

|||||||||