The Story Of One Of The 91st SRS COs,

|

||||||||||

| I became the squadron Operations Officer in mid- January. General LeMay’s daily staff meeting was held at 1 PM every day. The normal procedure for him was first to receive the weather briefing, next the results that our photo planes had obtained that day and the photo missions planned for the following day. Then, he continued his discussions with his command operations staff to make the decisions on the next day’s and future bomber efforts. The first day that Gen LeMay held his briefing on Guam, my C.O., Lt Col. Pat McCarthy took me with him to the 1 PM briefing. After the weather briefing, he turned to my C.O .and asked, “What’s wrong with reconnaissance?” My C.O. turned to me to answer the question. I told General LeMay that I thought our crews knew how to do their job, but were being told not only what to do, but how to do it. The General then reached into his uniform pocket and handed me a piece of paper. “Here is a list of 100 cities in Japan that I want complete photo coverage in seven days. Captain, you show me that you can do your job and you and I will get along fine.” We obtained the requested coverage within five days and I did get along very well with the General. I was privileged to brief him at those 1 PM briefings for the rest of the war every day that I was not flying with my crew. I would leave the meeting immediately after briefing the recon status. General LeMay had a great operations staff of future Generals that included Colonel John B. Montgomery and Colonel William “Butch” Blanchard and Col. Jack Catton.

Our 3rd Photo Recon Squadron staff spent the mornings planning the next days missions and working with the 21st Bomber Command intelligence staff in reviewing film to set priorities and objectives. After the afternoon Bomber Command briefing, I returned to our operations area where we briefed our crews that would fly missions the next day. |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

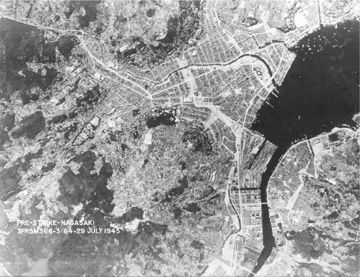

Below: Poststrike Photo of Hiroshima |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Below: Poststrike Photo of Nagasake |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

post-strike photos for your viewing as attached pages to this chapter. You may access them by clicking here with an easy return to this page. |

||||||||||

| Later in the afternoon, we debriefed the crews returning from that days missions. We used a simple radio code from our airborne aircraft to tell us after leaving the Japanese coast, the results of their days objectives. That information enabled me to know the approximate results of the days efforts prior to attending the Bomber Command 1PM briefings. Our lives continued in this vein for the next several months. We lost far fewer aircraft and crews than had been planned for. Thus our inventory of aircraft and crews continued to grow. The men, enlisted and officers built first an Enlisted Mens Club and an Officers Club thanks largely to the power that our whisky supply in obtaining lumber and all necessary material. Movies, USO road shows and swimming within the reef of Tumon Bay provided some recreation for our men. |

||||||||||

| We did all the pre-invasion photography prior to the Okinawa campaign. Interesting, the most valuable photography turned out to those providing the water depths in the harbors that the Navy utilized for the landings and support for the troops once ashore. With the taking of Iwo Jima, the squadron acquired a flight of four B-24s specially equipped electronic surveillance planes that operated out of Iwo Jima against the radars and communications in Japan. They provided a valuable asset. Iwo Jima also provided a safe haven for several of our planes that encountered mechanical problems that would have prevented them from returning to our Mariana Island bases on Saipan, Tinian and Guam. Being able to land on Iwo for repairs and/or fuel was a Godsend to not only bomber crews but also several of our recce crews We also sent a flight of four F-13s to the island of Moraoti to map Java for General MacArthur.. At the end of July, I was ordered to send two of our top crews to Tinian. I was not informed of what they were to do. Don’t ask. One of them wound up 15 minutes behind the Enola Gay on its historic drop of the first atomic bomb on August 6th. It also happened by coincidence that I had another plane near Hiroshima that took pictures of the atomic cloud. |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| I had no idea what was happening until after the drop. As there was no adequate photo lab on Tinian, the decision was finally made late that evening to bring the film to our lab on Guam. I wound up flying a C-45 to Tinian that night, picked up the film, returned to Guam and stayed with the film at the lab until the pictures were developed. I delivered the photos to General LeMay’s quarters at about 2 AM and left them with his aide. The next day, my crews were asking to see the pictures but I could not authorize them to see them. Ironically, one of those pictures made the cover of Life Magazine the following week. My initial reaction to these crews? Man is either going to have to learn to live with man, or we will not have a world. My promotion to Major had come thru just before the first atomic bomb was dropped. I flew my last F-13 mission three days after the Nagasaki atomic bomb drop. The weather at Nagasaki had been bad since the drop and post strike results were urgently needed. I first flew more post strike photos over Hiroshima at high altitude and then flew down to Nagasaki. Nagasaki was still cloud covered so we let down to below 1500 feet before breaking thru the overcast to obtain good pictures of the results of that bomb. We had no fighter action against us. I was named for my Mother’s youngest brother, Clarence Emerson Cole. He served in the Navy in WWI at age 16. So he lied about his age! He also served in WWII as a Chief Petty Officer aboard an APA, an attack transport for troops. He found me, I don’t know how, on Guam in the spring of 1945. I was able to give his skipper, exec and him a ride on one of our F-13A staging flights from Harmon Field to North Field. In return, several of our officers were invited aboard their ship for dinner. We were served steaks that covered the whole plate. What a treat! A few days later, I had a call from my Uncle Clarence asking how much refrigeration space we had. I told I would find out and call him back. When I did, he informed me that his ship had been ordered back to Pearl Harbor and they had to give the 50% emergency rations to either to the Island Command or anyone with proper storage space. He told me to send two 6x6 trucks down to the dock. They returned loaded with sides of beef, hams and turkeys. Our squadron ate like kings for the next few weeks. General LeMay and several of his staff came over to eat with us once during that period. He told our C.O. that we were eating better than he was. But I must now tell you how we happened to come by that refrigerated space. As I indicated earlier, the Seabees controlled most of the “goodies” on the island. We were able to obtain three 10'x10'x10' walk in refrigerators in return for three cases of the whisky that we had brought from Smoky Hill Air Base, Salina KS, purchased with $1,000 of the $1,300 given to us by the Officers Club when they cut a melon prior to the departure of each unit that trained there. We had not opened our stash while on Saipan, but used it judiciously to obtain lumber and other comforts of life after we moved to Guam. While I was on Guam, my wife Dottie had given birth to our first baby on February 27th. Dottie, named him Gary. A breach birth six weeks late. I didn’t get to see them until early December. I had returned to the states via C-54 in October and after a minor operation and recovery in a Denver military hospital, I was released from active duty at Fort Logan, outside Denver, CO. where I took the train to Salina from which I had departed more than a year earlier. |

||||||||||

|

Go to Chapter 8 1 — 2 — 3 — 4 — 5 — 6 — 7 — 8 — 9 — 10 — 11 Cover Page — Introduction — Table of Contents Or you may go to Home - Contact Us - Cold War Hist. - 91st SRS Hist. - Stardust 40 Mission Story |

||||||||||